The Ultimate Guide to Innovation Teams

BECAUSE INNOVATION IS A TEAM SPORT

BECAUSE INNOVATION IS A TEAM SPORT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Today, large organizations face an imperative to innovate. The accelerating pace of change, shifting consumer demands, and globalization make innovation unavoidable. And with the impressive market returns of the most innovative companies – from Apple to Google to Netflix – innovation is highly desirable. For these reasons, there is increasing interest in how organizations can improve their capacity to innovate and better manage the innovation process by designing innovation teams.

At the same time, work has become increasingly collaborative. This is due to several factors, including the increasing complexity of products, the changing generational make-up of the workplace, and ubiquitous web-based collaboration tools. With today’s complex products – from smartphones to smart foods – no single employee has the knowledge to develop all of the components. This necessitates large teams to conceive and bring these products to market.

And with Gen X, Gen Z and Millennials making up so much of the workforce today, there is an expectation that individual employees can contribute and will be heard. Finally, collaborative tools – from Zoom to Slack – have become commonplace, making teamwork more feasible. For these reasons, 80 percent of companies with more than 100 employees use a team-based approach, and in innovation settings, this ratio is even higher (Kratzer et al.). The amount of time employees spend engaged in collaborative work has increased roughly 50 percent and takes up 80 percent or more of their time (Cross et al.). And according to a Microsoft study, we are on twice as many teams as we were five years ago (Wright et al.).

Given this trend, it is surprising that so little is known about designing and managing innovation teams. This is a serious gap in corporate innovation management given the imperative to innovate and ubiquitous nature of teams in work today. The Ultimate Guide to Innovation Teams aims to at least partially fill that gap. We have pulled together multiple research studies, many of which are not available to the general public, to summarize what is known about high performing innovation teams.

First off, there are a number of limitations to innovation teams research:

Despite the limitations of innovation team research, there are several useful concepts underpinned by thoughtful research. Let’s start by defining what an innovation team is. An innovation team is a group of two or more persons whose purpose is to deliver new ideas, new methods, new approaches, new inventions, new materials and/or new applications that drive value in the market.

An innovation team is a group of two or more persons whose purpose is to deliver new ideas, new methods, new approaches, new inventions, new materials and/or new applications that drive value in the market.

Traditionally, innovation teams were R&D teams, usually located at company headquarters. The members had deep technical and scientific knowledge. But over the past twenty or so years, nudged by the Open Innovation movement, companies have expanded their innovation efforts beyond R&D.

Today, innovation occurs in research, packaging, marketing, logistics, and every process and location of the business. So today, innovation teams are cross-functional, often virtual, and exist across the full range of company functions. In fact, Thomas Igeme of LinkedIn said, “Innovation teams need to be thought of differently, and the number of teams that can afford not to be innovation teams is dwindling.”

Innovation teams need to be thought of differently, and the number of teams that can afford not to be innovation teams is dwindling.

The role of “regular teams” is to sustain and maximize existing products and revenue streams in order to exploit the organization’s existing advantages for as long as possible. Innovation teams differ from regular teams because they are, by definition, creating something new. Thus they operate in greater uncertainty. There are often few rules or guardrails for innovation teams. And not everyone thrives in uncertainty.

There are structural differences as well. Sometimes innovation teams work outside of the everyday operations of the “mothership,” the core, existing business. This can pose additional challenges such as limiting their access to resources and rapid feedback. And even when innovation teams succeed at developing a novel concept, they face barriers to acceptance, because change inevitably threatens the status quo.

Finally, because of the greater uncertainty involved, innovation teams tend to oscillate between inductive and deductive processes. So as Thomas Ikeme says, “Where ordinary teams work at a steady pace, innovation teams are more ‘wavy’.” These are just a few of the ways in which innovation teams are different from regular teams.

Like any teams, innovation teams need the relevant functional skills related to the project. But innovation teams also need specific “soft skills,” and these skills differentiate them from regular teams. At the most basic level, innovation teams need the same skills that individual innovators need to succeed.

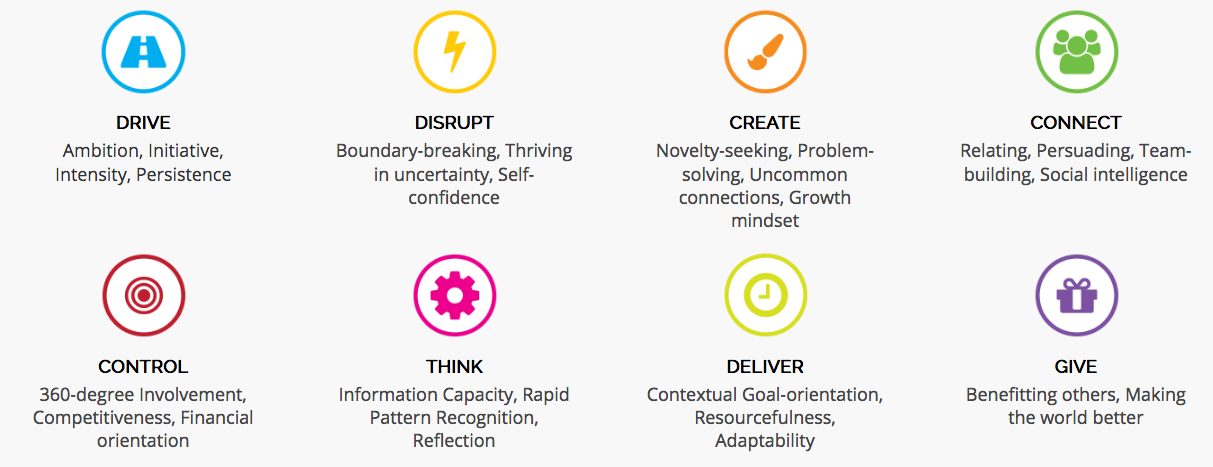

A large-scale study on innovation outcomes was performed across numerous industry segments. It was conducted on a large international sample of serial innovators and a general population control group. The research, over four waves, revealed eight behaviors or innovation talents that distinguish serial, successful innovators from the general population. These eight behaviors are highly predictive of real-world innovation outcomes such as profitability, global expansion, acquisitions and IPOs. In order to thrive, innovation teams need to be made up of individuals with a sufficient degree of these skills.

Let’s first look at these eight skills that innovators need in general, then we will pick up on the impact of leadership and touch on several additional dimensions that impact innovation teams.

Here is a brief summary of the eight innovation skills:

You can delve into more detail on the eight innovation talents, and learn about innovators who embody each of these talents, in this simple guide.

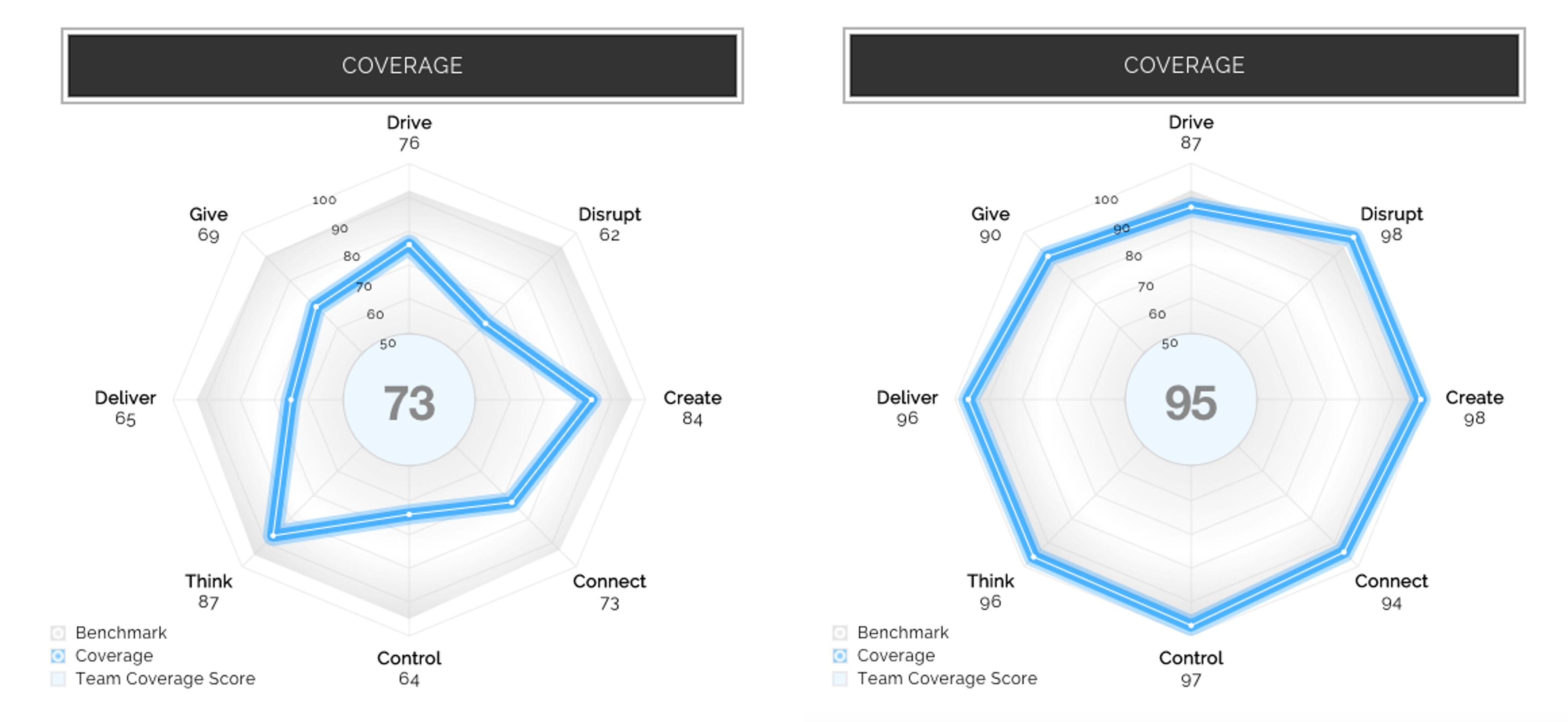

Innovation teams with coverage of all eight innovation talents out-perform those with gaps. You can easily strengthen a team with gaps by adding team members, mentoring and training. Read more about innovation training here.

A weak team (left) lacks Disrupt, Control. and Deliver skills.

A strong team (right) has coverage of all eight critical innovation talents.

So far we know that: (1) innovation teams operate in very different conditions than regular teams; and (2) innovators have very distinct skills from regular workers. Despite this, organizations tend to form innovation teams in much the same way as they form regular teams. They tend to assemble team-members based on their functional skills and/or with representation from different functions, such as R&D, finance, and marketing.

But as Thomas Ikeme pointed out, “Where functional skills and expertise drive ordinary teams, mindset and intrinsics rule the day on innovation teams.” We can’t agree more. Clearly we need to form innovation teams taking into account intrinsics, such as those captured in the eight innovation skills above.

At the skill level, there are several key points to keep in mind:

So far, we have discussed the innovation skills of team members. In addition, leadership is one of the most important factors in the outcomes of innovation teams. While leadership may not be enough to overcome individual team-members’ native talents, or the force of outside context, it can make the most of both. As with innovation teams in general, the research on innovation team leaders tends toward small studies. However, there is statistical evidence that certain leadership approaches are correlated with innovation team outcomes.

The first body of research surrounds what is called “Transformational Leadership.” This approach (put forth by Bass, 1985) describes leaders who encourage team members to perform above and beyond expectations by:

Subsequently, the concept of Ambidextrous Leadership has been proposed and blossomed into a movement in innovation circles. Ambidextrous Leadership describes a leader’s ability to use both “Opening behaviors” and “Closing behaviors” and flexibly switch between the two. Opening leadership behaviors include:

Whereas Closing Leadership behaviors include:

An Australian study found that Opening leadership behaviors positively and significantly predicted team innovation, especially when Closing leadership behaviors were also strong (Zacher et al.). Team innovation was highest when both Opening and Closing leadership behaviors were strong, as opposed to when only one was strong, or both were weak. Opening and Closing leadership behaviors predicted team innovation more than a Transformational Leadership style.

While the results of this study are intriguing, one wonders whether the researchers distinguished between the innovation phases in their survey. Certainly, Opening leadership behaviors are more important during the conceptual phase of innovation; and Closing leadership behaviors are more crucial during the Implementation phase. Once you have your rocket ship ready to launch and are counting down to blast-off, you can’t be experimenting with core designs and materials. By then, all systems must work as designed and be bullet-proof. So when applying this theory to your teams, we would introduce more nuance in applying the behaviors to the innovation phases.

Also we believe there is an important distinction between “top-down, ‘command and control’” leadership and “Closing leadership behaviors.” For innovation teams to succeed long-term, leaders must empower them, vs. controlling and punishing them. ‘Command and control’ leadership imposes a top-down decision on teams, whereas coaching models and supports the teams’ own good decision-making skills and habits. Great innovation leaders don’t catch their teams a fish, but rather, they teach them to fish.

On the topic of leadership styles, we are privileged to speak with a great innovation leader: Evren Eryurek, Director of Product Management at Google Cloud, and former SVP & CTO of GE Healthcare. Evren knows from experience how leading innovation teams differs from leading ordinary teams. He says, “The top leader has to be the right person for any innovation to work. A ‘command and control’ style doesn’t work, in my opinion. Instead you need to Inspire, Coach, and Empower, in that order. And you have to be present globally for teams, encourage them to take risks and walk the talk. If you cut their budget in the first financial challenge, then you demoralize innovation teams.”

Let’s unpack Evren’s sage advice:

Innovators, more than regular employees, tend to be mission- and vision-driven. And an inspiring mission ignites teams’ ambition to reach for 10x better goals, and the grit and persistence to reach them. To inspire an innovation team, ask them to explain their Massive Transformation Purpose (or MTP) in ten words or less. Then mirror that mission back to them when they are at a crossroads about a feature or business model. Which decision aligns with their MTP? Push them to be not 5 percent better, but 10x better than the competition or any substitute – not only in their product, but also in their business model, marketing, and culture.

A coach is more of a peer or mentor than a top-down manager. As a coach, it is better to ask the innovation team questions than to tell them what to do. Ask what experiments they have conducted and what they have learned from them. Ask them what product-market fit will look like, and what metrics they are using to detect if they are approaching this Holy Grail state. Do they need 10 enterprise customers, or 1 million freemium subscribers to demonstrate product-market fit? How many daily active users, and what percentage of customers need to renew or upgrade? Ask the kinds of questions that lead them to think through their assumptions. Encourage them to pay attention to real data, not donning “happy ears,” only hearing what they want to hear.

We believe that innovation teams do not perform well under tight, top-down management and demands for frequent, conventional reporting. This is not because they are such unbridled free spirits. It is because innovation teams often operate in greater ambiguity, at accelerated speeds, and on different metrics than the main business.

If you ask an innovation team for a 10-year inflation-adjusted revenue projection of their new product when it is only a minimum viable product (MVP), you are wasting your time and theirs. Even if they comply, there is about a two percent chance the projections will be accurate. But you just took the team away from the more important work of testing their MVP with potential customers. Instead of “managing.” which conveys a sense of control over the teams, you are better off empowering innovation teams to make customer-centric decisions.

Leading an ordinary team requires the leader to Manage, Coach and Inspire, in that order. Whereas with innovation teams, one needs to Inspire first, then Coach, then Empower.

— Evren Eryurek, Google

So far we have discussed the skills of individual team members and the impact of leadership, In addition, there are several other dimensions that come into play when innovators are assembled as a team, These include diversity, conflict, friendliness and network effects.

Recently, there has been more appreciation of the role of diversity in innovation teams. In an effort to create mental diversity, which can increase team creativity, many companies try for demographically diverse teams. This approach involves including historically underrepresented groups like women and non-whites, or diverse age groups, on teams. However, there is debate around whether demographic diversity really brings mental diversity.

A study published in Harvard Business Review found a difference between inherent and acquired diversity. Inherent diversity involves traits you are born with, such as gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Acquired diversity involves traits you gain from experience. In a meta-analysis of 30 years of research, it was found that having teams with innate diversity (gender, age, ethnicity) is not enough (Hewlett et al.).

Let’s be 100 percent clear: Diversity and inclusion are the right things to do for social equity reasons alone. But true diversity is more than skin-deep. The HBR article refers to 2-D diversity as the presence of both inherent and acquired diversity. Companies with 2-D diversity out-innovate and out-perform others. “Employees at these companies are 45 percent more likely to report that their firm’s market share grew over the previous year and 70 percent more likely to report that the firm captured a new market.”

Developing the eight innovation skills can enhance acquired diversity: e.g. developing employees’ ability to relate to diverse stakeholders, respond to emerging patterns, synthesize diverse sources of data and thrive in ambiguity. Instilling these innovation skills in your workforce may just be a shortcut to acquired diversity and achieving 2-D diversity.

There is a widely-held belief that divergent opinions and perspectives increase the creative performance of innovation teams. Indeed, disagreement can benefit teams by generating more flexible thinking, deeper consideration of options, new approaches, and a better understanding of issues.

A very thorough piece of research was done on the impact of conflict (or “team polarity”) on innovation team performance. It was found that in the upfront, conceptualization phase of innovation, polarity positively influences creative performance of innovation teams. However, in the backend or commercialization phase, and in tasks with lower degrees of complexity, polarity negatively impacts the creative performance of innovation teams (Kratzer et al.).

The researchers also categorized innovation team tasks according to the degree of change they involved from the current product or process. They found that polarity hinders teams doing tasks with low product or process change, because polarity hinders efficiency.

When a high degree of product or process change is involved, polarity improves team performance…up to a certain threshold. The relationship is a Goldilocks situation, where the bed needs to be neither too soft nor too hard. In more scientific terms, the relationship is described with an inverted U-shaped curve.

An earlier study on polarity in virtual product development teams found that the relationship between polarity and performance varies across eight different issues (Engelen et al.). The eight issues are based on NewProd, a method that predicts market success of new products with 84 percent accuracy. NewProd lists eight issues that predict market success, including:

The researchers measured team polarity on these same eight issues. They found that the effects of polarity tend to vary by the issue itself:

The researchers conclude that team managers should try to prevent polarity (team debate) about the issues that decrease team success. However, to us, the underlying issue here does not seem to be the team disagreement, but the fact that a new product simply must have these qualities to succeed in the market, regardless of the team’s opinions. For example, a product should be superior and unique, and must have economic benefit to the customer, whether the team believes it has or not. High levels of team disagreement on these fundamentals perhaps suggests that the product is not clearly superior or unique and does not clearly benefit the customer, conditions which are hard to overcome.

One final point on team conflict that we wish could go without saying. Interpersonal conflict, which is conflict aimed at a person’s being, is always toxic. Whereas conflict aimed at the content of the agenda can be productive. As Google found in its Project Aristotle in the report, “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team”, leaders should create “psychological safety” on their teams and promote conversational turn-taking so that members feel safe offering ideas and input. Nothing kills psychological safety faster than the fear of personal put-downs or attacks.

A very novel piece of research focused on the impact of friendly and friendship relationships on innovation teams (Kratzer et al.). Think about how common this stereotype is: the innovation team plays billiards together on breaks and goes out for beers on Friday nights. The difference between “friendly” and “friendship” is that friendly relationships involve informal, non-work-related interactions at work but keep it at the surface; whereas friendships involve an emotional connection and time spent together outside of work. This research confronted two opposite theories on friendliness and innovation teams: on the one hand, friendliness is supposed to increase team cohesiveness; on the other hand, it leads to distraction, groupthink and free-riding.

The research found that both very low and very high levels of friendly, non-task related communication impede innovation team performance. It seems this is another case of “Goldilocks.” A team so formal as to exclude all non-task related communication would not be very stimulating or creative. On the other hand, too much non-task related communication means nothing is getting done.

However, the research found that friendship relationships had positive effects on innovation team performance. Because the interactions take place outside of work based on genuine interest in the other person, it speaks to a deeper bond and does not impede focus at work.

In addition to certain skills, and the right mix of conflict and friendship, innovation teams clearly need rapid access to information and knowledge. Access to information and the ability to discuss new knowledge with other teams can accelerate or hinder innovation team success.

A very interesting study looked at the position of various innovation teams within a global network, measuring their access to information, the flow (uni-directional or reciprocal), and whether the team, on balance, sends or receives more information (Leenders et al.). Do they tend to go to the nearest source for information, or do they seek out varied sources, even if those sources are less efficient? The study discusses three concepts: centrality (the location of each actor in the network), centralization (the degree to which a group depends on one or a few actors); and degree (the number of ties an actor maintains).

The more creative teams used more diverse sources of information – not only the shortest, most direct route to information. The more efficient teams, in contrast, stuck to the more convenient information sources, but were less creative.

The more creative innovation teams used more diverse sources of information, not only the shortest, most direct route to information.

This finding makes sense. The research on individual innovation talent, mentioned above, found that Information Capacity, Novelty-Seeking and Relating skills are highly correlated with success in innovation. One wonders whether teams with a high degree of these traits in their members might seek out more diverse sources of information, regardless of their position in a network.

This finding about information exchanges aligns with another study of high-performing teams (though not specific to innovation teams) (Pentland). This study found that three factors explain team performance:

Feedback on team interactions over the course of the study improved team performance.

This study used physical sensing devices worn by team members, which is cost-prohibitive at large scale, intrusive and, with virtual teams, impractical. In our view, a more fundamental study is needed to predict team energy, engagement and exploration before the team is formed. What psychographic traits predict team energy, engagement and exploration? What traits in the team leader encourage team energy, engagement and exploration?

In conclusion, the interaction of individual team members’ skills, leadership style, and contextual factors can produce an almost infinite number of dynamics on innovation teams.

An innovation leader should focus his/her attention on:

Here are the fifteen key points in this article:

Innovation is becoming an imperative to firms’ survival, and teams are the default form of work today. So the ability to design and manage innovation teams is an important topic in corporate innovation. We hope that this brief overview of some of the key ideas in innovation team research both stimulates you and saves you years of trial and error.

Cross, R. et al. “Collaborative Overload.” Harvard Business Review, 20 Dec. 2016, hbr.org/2016/01/collaborative-overload.

Engelen, Jo M. L. Van, et al. “Improving Performance of Product Development Teams through Managing Polarity.” International Studies of Management & Organization, vol. 31, no. 1, 2001, pp. 46–63., doi:10.1080/00208825.2001.11656807.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann et al. “How Diversity Can Drive Innovation.” Harvard Business Review, 1 Aug. 2014, hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation.

Kratzer, J., et al. “Informal Contacts and Performance in Innovation Teams.” International Journal of Manpower, vol. 26, no. 6, 2005, pp. 513–528., doi:10.1108/01437720510625430.

Kratzer, J., et al. “Informal Contacts and Performance in Innovation Teams.” International Journal of Manpower, vol. 26, no. 6, 2005, pp. 513–528., doi:10.1108/01437720510625430.

Kratzer, J, et al. “Team Polarity and Creative Performance in Innovation Teams.” Creativity and Innovation Management, vol. 15, no. 1, 2006, pp. 96–104., doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00372.x.

Leenders, Roger Th.a.j., et al. “Innovation Team Networks: the Centrality of Innovativeness and Efficiency.” International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organisations, vol. 4, no. 4, 2007, p. 459., doi:10.1504/ijnvo.2007.015726.

Pentland, Alex “Sandy”, et al. “The New Science of Building Great Teams.” Harvard Business Review, 15 July 2015, hbr.org/2012/04/the-new-science-of-building-great-teams.

Wright, Lori et al. “New Survey Explores the Changing Landscape of Teamwork.” Microsoft 365 Blog, 22 Jan. 2020, www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2018/04/19/new-survey-explores-the-changing-landscape-of-teamwork/.

Zacher, Hannes, and Kathrin Rosing. “Ambidextrous Leadership and Team Innovation.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2 Mar. 2015, www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/LODJ-11-2012-0141/full/html.